The Statue of Liberty

as Promise

At the Statue of Liberty’s feet lie broken shackles. What do they mean? For Emma Lazarus in her poem “The New Colossus,” the chains might be the oppression that immigrants experienced in their countries of origin: “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” But this was not the original meaning.

The original impetus for the statue came from Edouard Laboulaye, a politician and intellectual who was a committed abolitionist and a proponent of women’s rights. “Liberty Enlightening the World” was to commemorate French contributions to the United States, certainly, but also the victory of the Union in the American Civil War and the emancipation of the enslaved. When Auguste Bartholdi accepted Laboulaye’s commission in 1871, the design of the statue was very much managed by Laboulaye, with Bartholdi submitting models to him for his approval. Originally, Laboulaye wanted the statue to hold the broken shackles, but acquiesced to the current design where the shackles lie by her feet (Smith 2021). In any case, the abolitionist foundation for the Statue of Liberty was structured into the work from the beginning. Only later–after the establishment of Ellis Island as the premier entry point for European immigration–did the Statue of Liberty take on the meaning of hope for immigrants to the United States.

Although the State moved away from the Statue’s emancipatory and abolitionist meanings, people did not. Many saw the Statue of Liberty as an ironic–and empty–promise of racial equality in a country where racial discrimination continued as a fundamental fact of life. Others tried to re-invest the Statue with its original meanings by utilizing Liberty Island as the backdrop for social justice movements and protests. These interventions extended beyond the racial politics of the United States itself to the policies and military campaigns of the United States abroad.

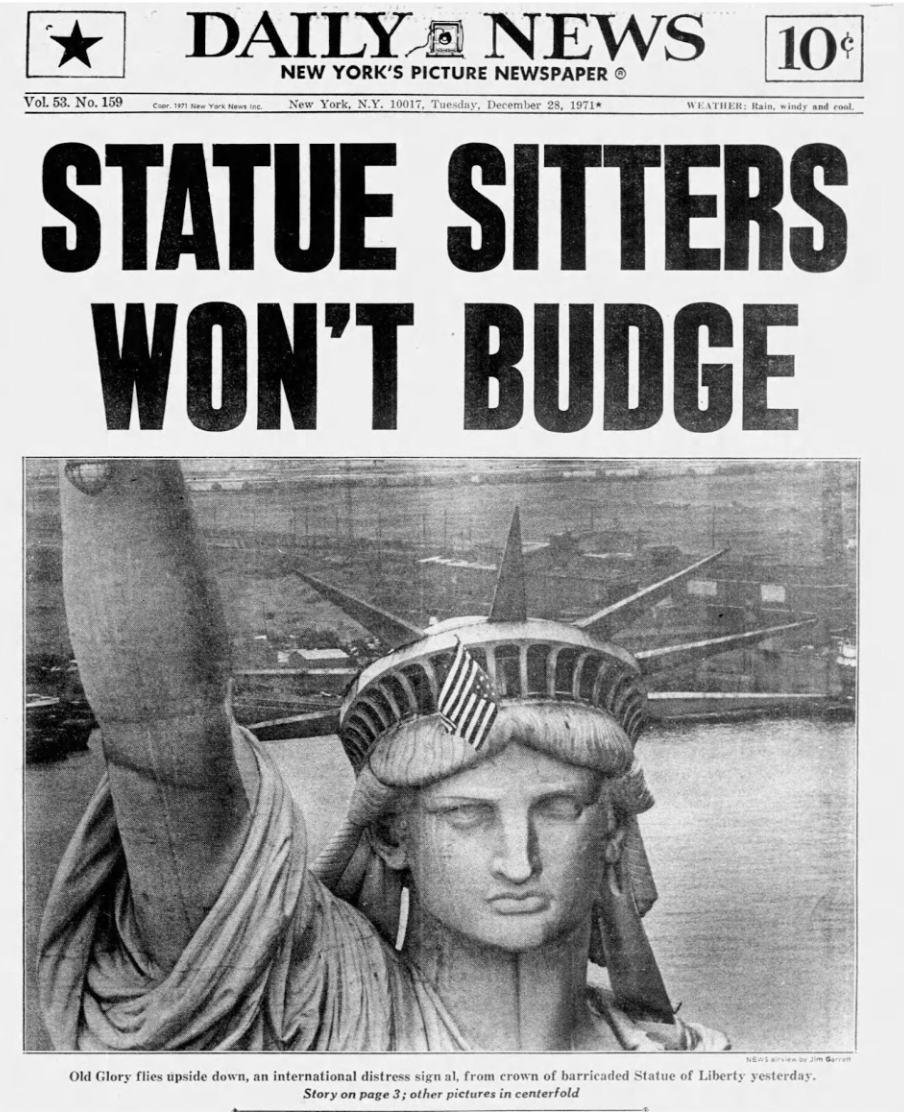

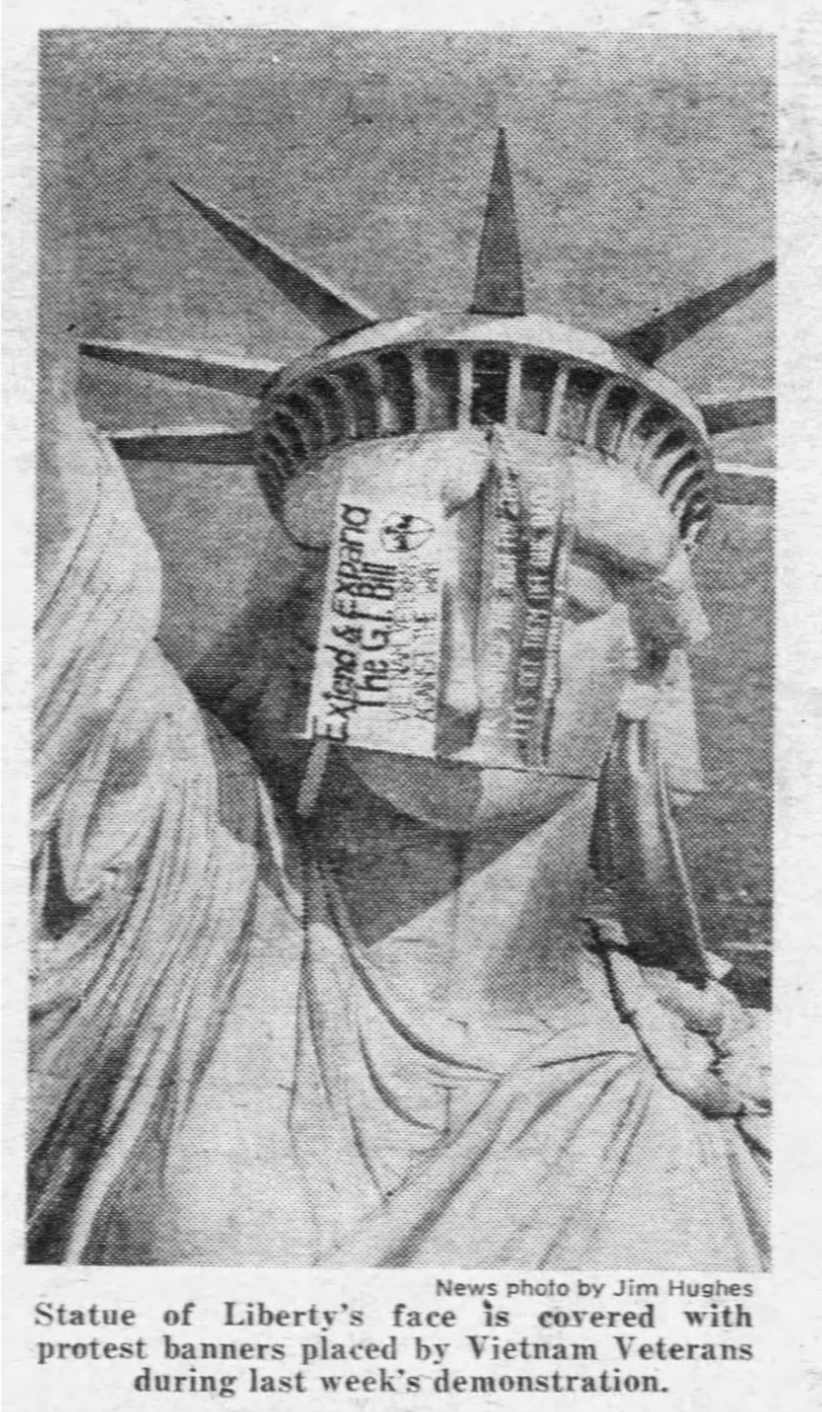

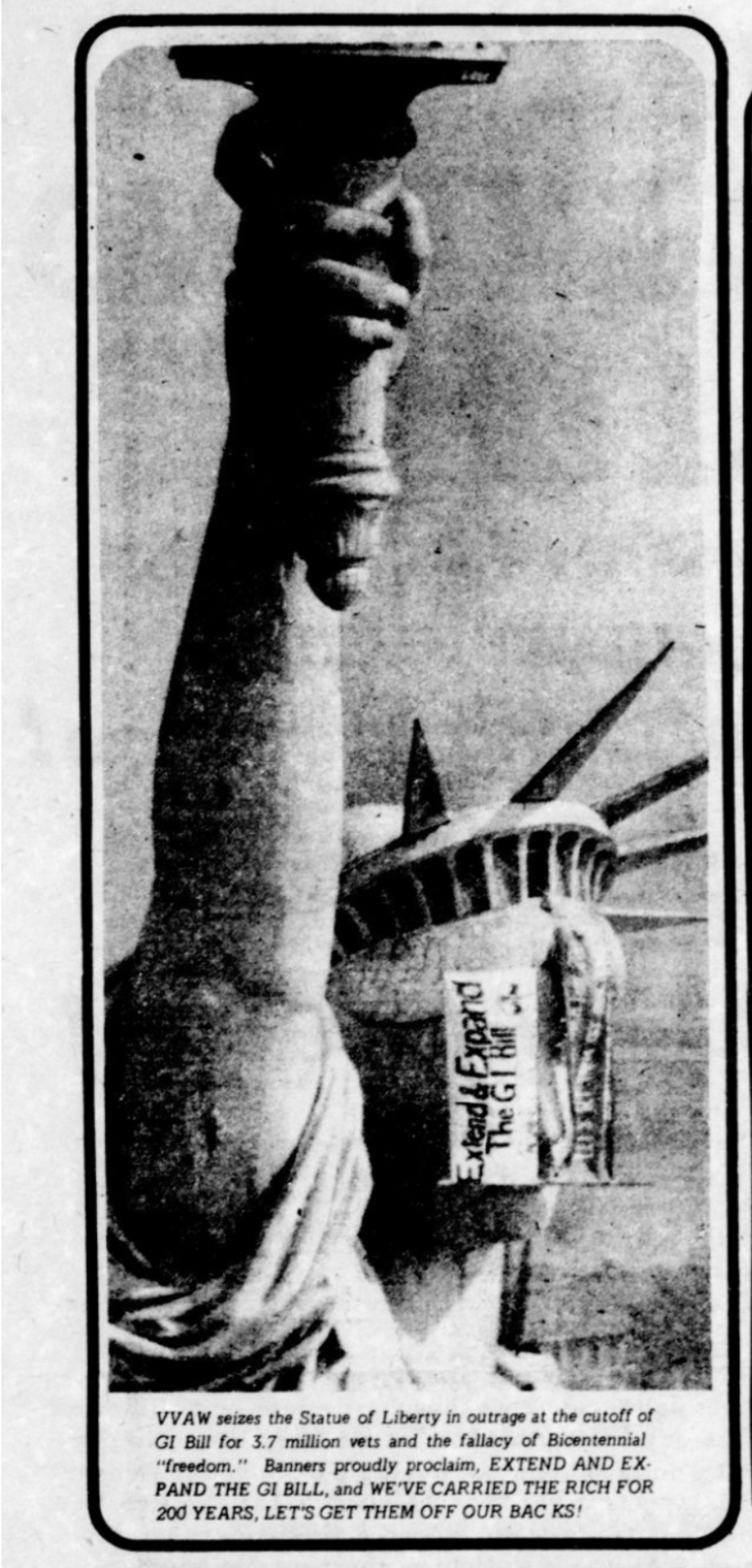

The images below are some of the press clippings, letters, photos and telegrams detailing a number of protests at the Statue of Liberty over time tied to other civil and human rights protests. Below the images are a number of stories and resources pertaining to these protests.

Antiwar Veterans protest at the Statue of Liberty

Antiwar Veterans protest at the Statue of Liberty

Antiwar Veterans protest at the Statue of Liberty

Antiwar Veterans protest at the Statue of Liberty

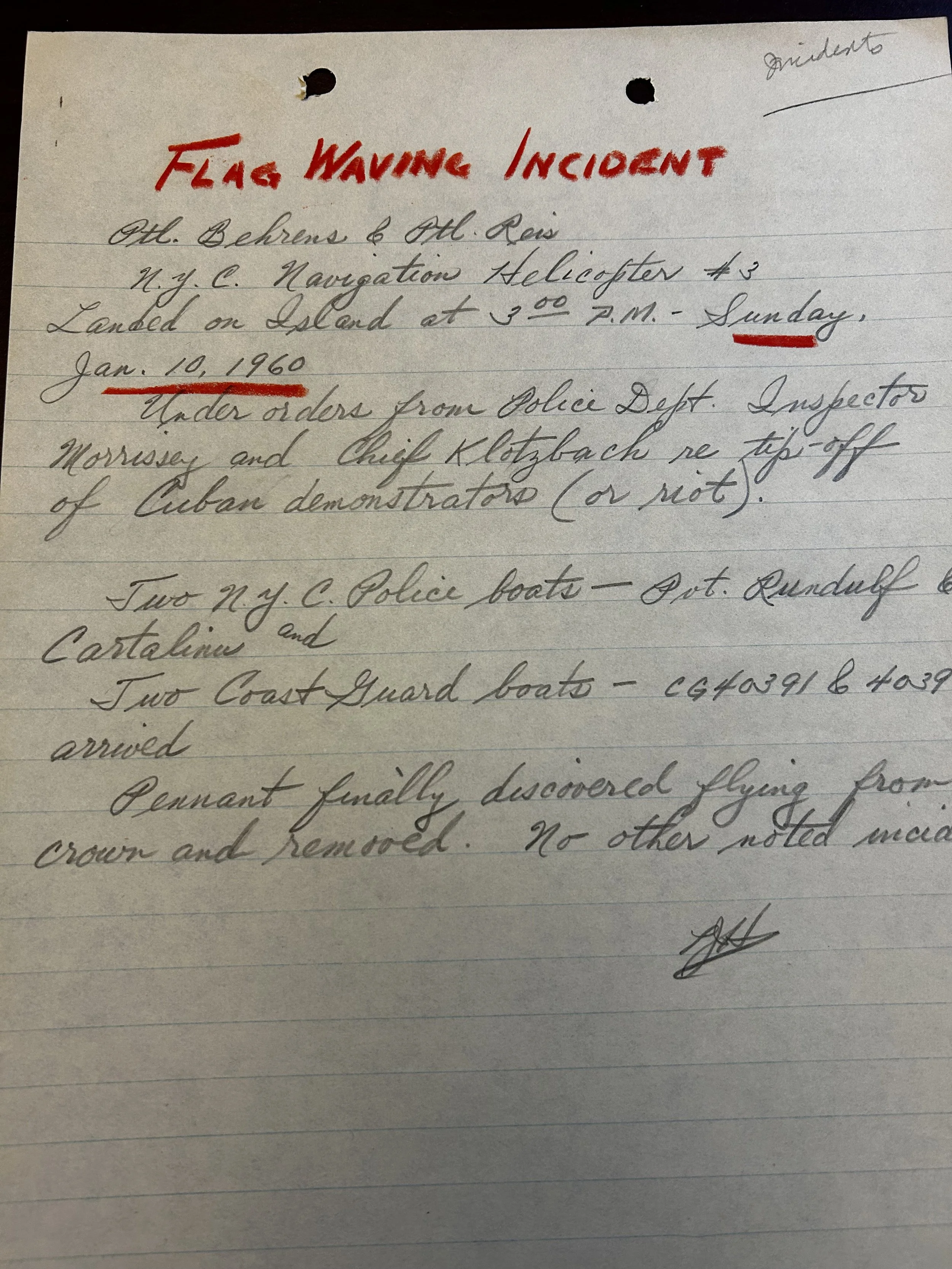

Note on a 'flag waving incident' at the Statue of Liberty

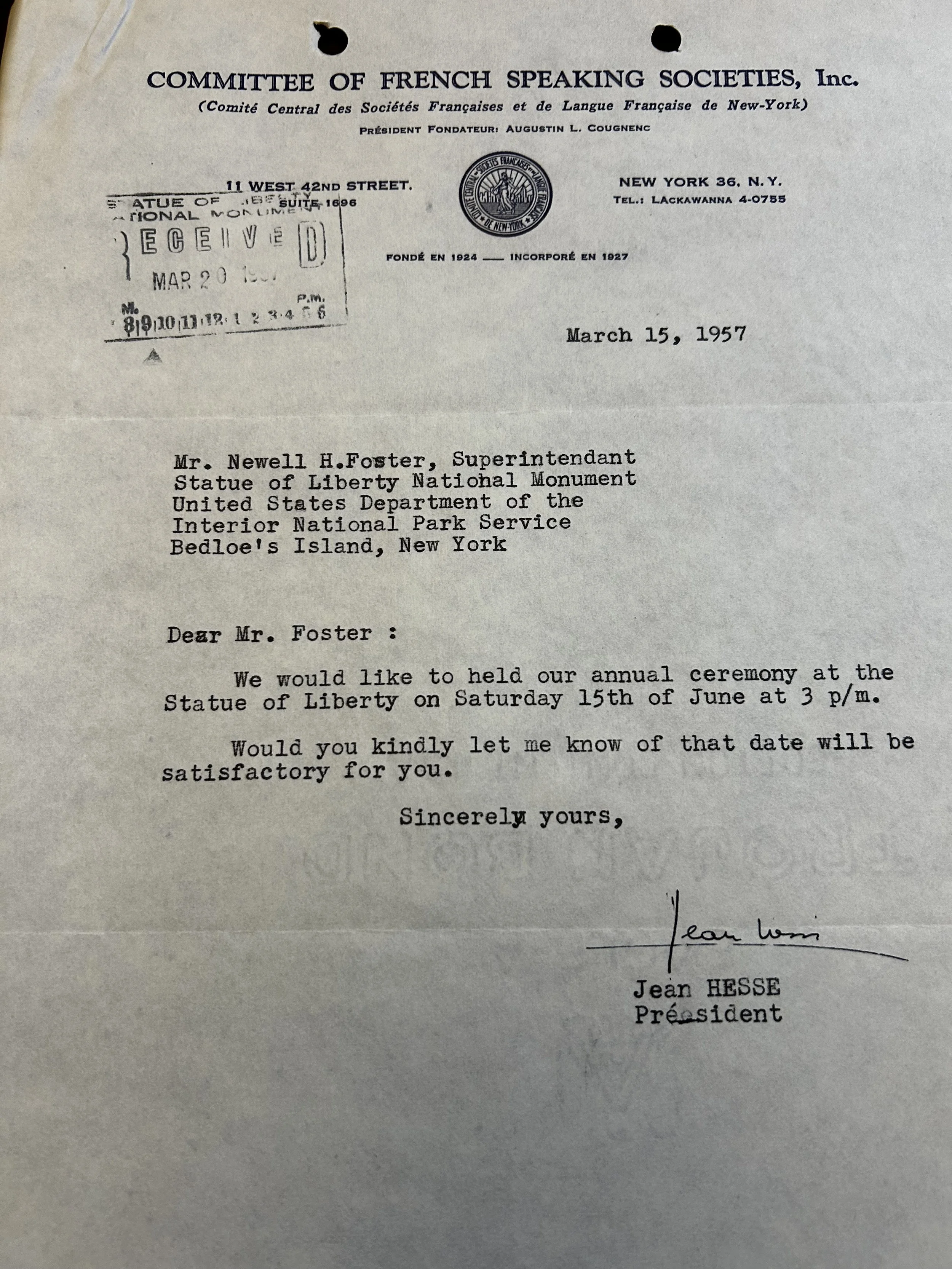

Letter requesting permission to hold a ceremony at the Statue of Liberty by the Committee of French Speaking Societies

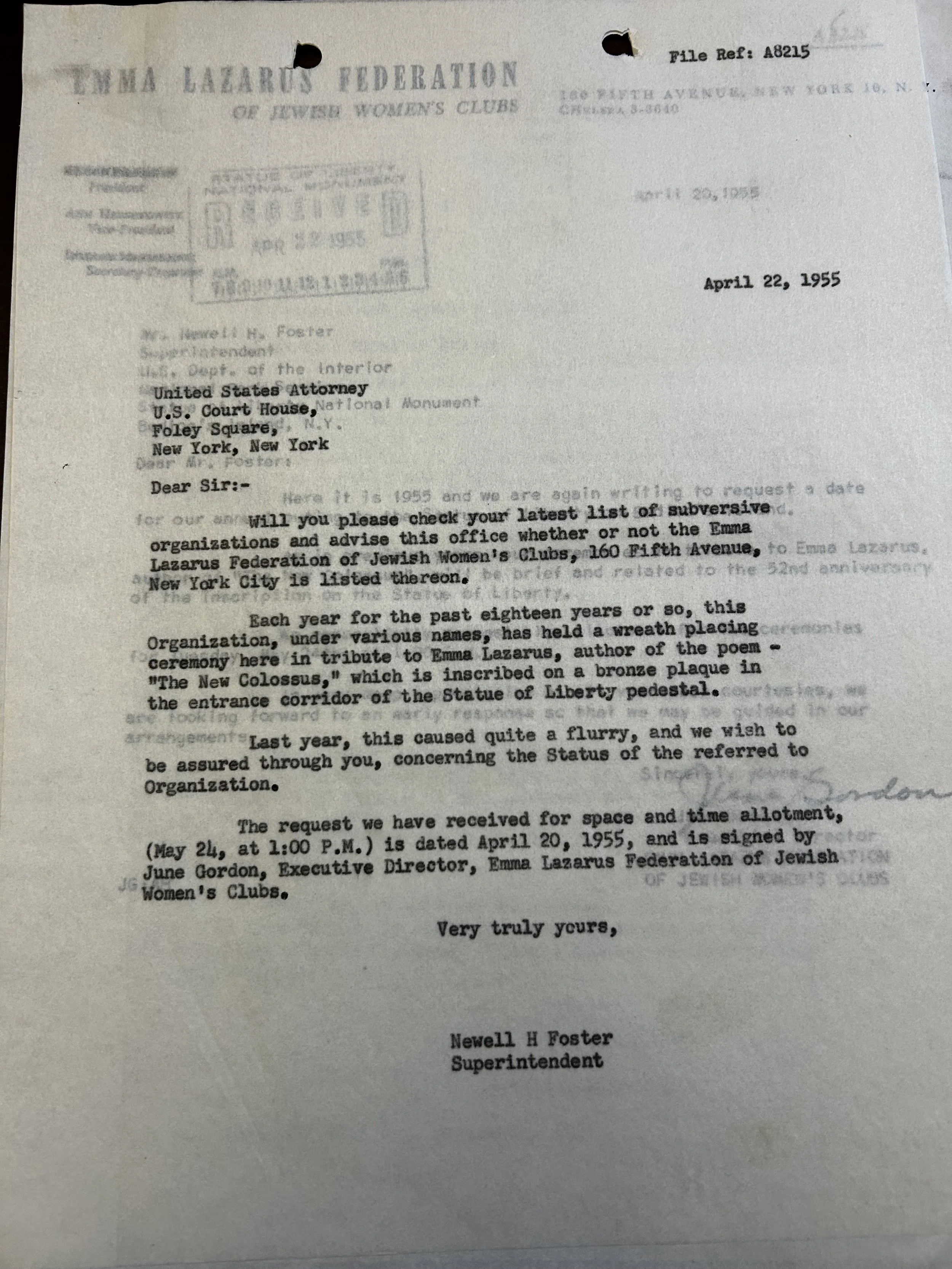

Letter from Superintendent of NPS Liberty Island site to the Attorney General regarding the status of the Emma Lazarus Federation of Jewish Women's Clubs as a possible subversive organization

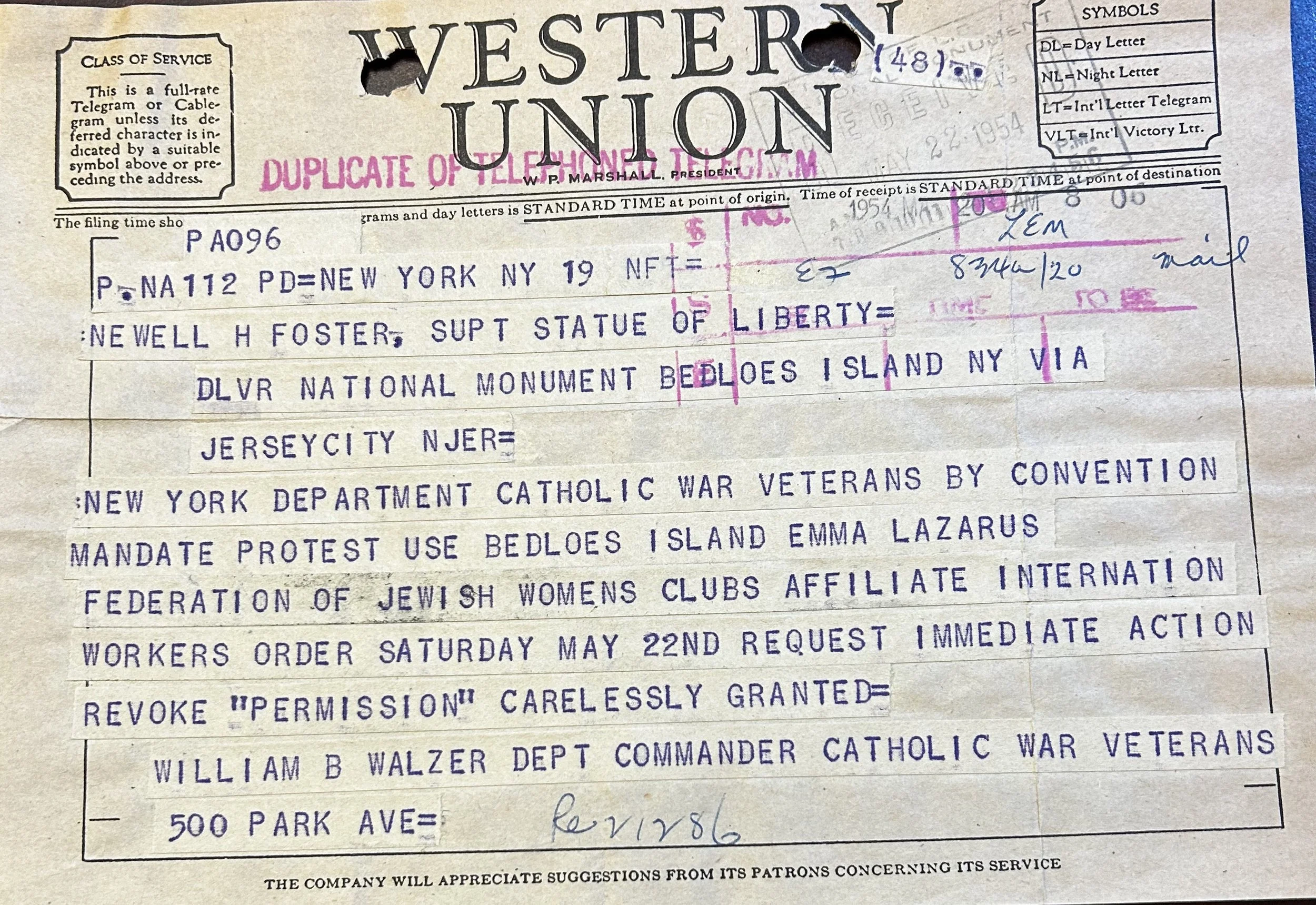

Telegram from Catholic War Veterans protesting a permit granted to the Emma Lazarus Federation of Jewish Women's Clubs

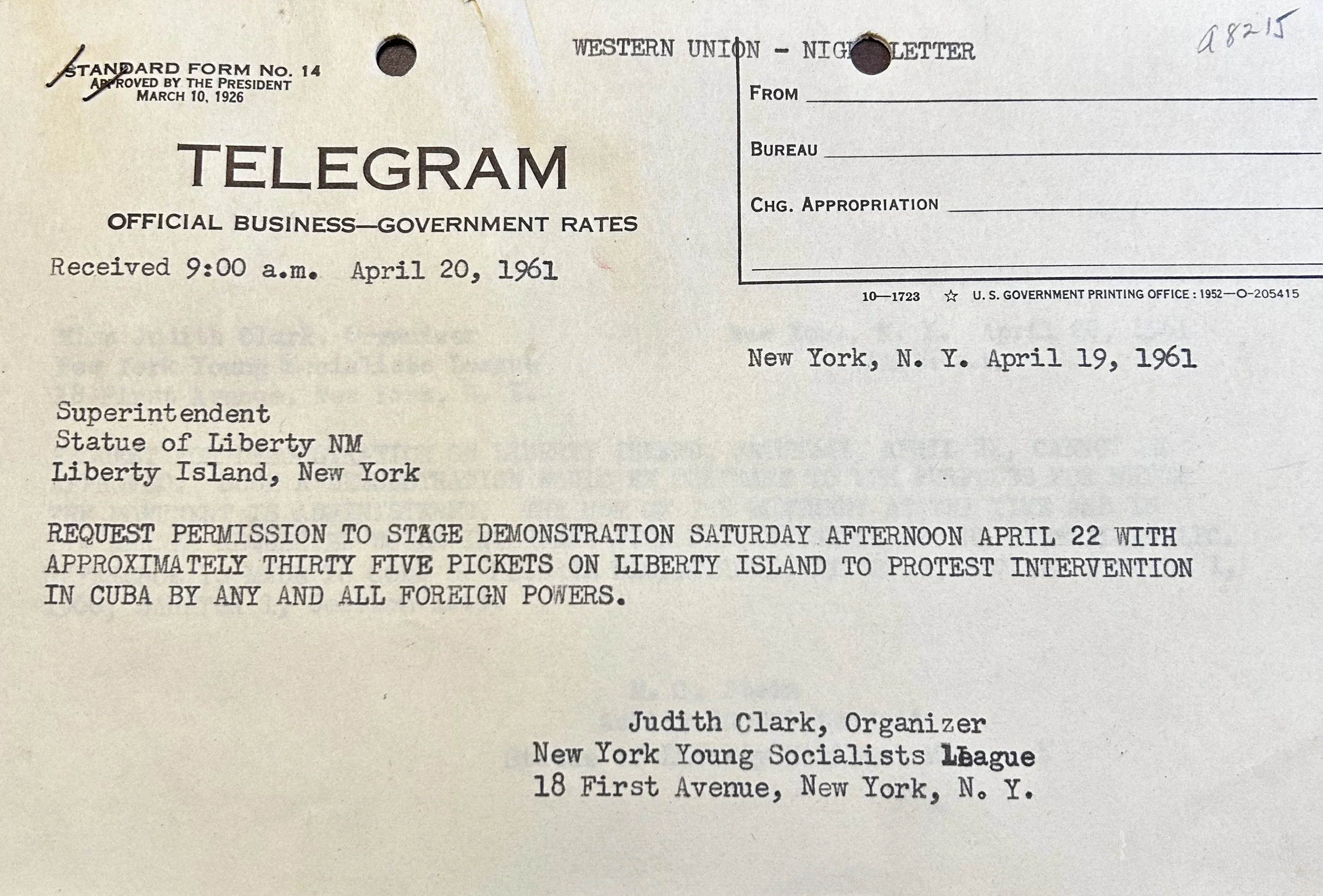

Telegram requesting permission to protest the occupation of Cuba by the New York Young Socialists League

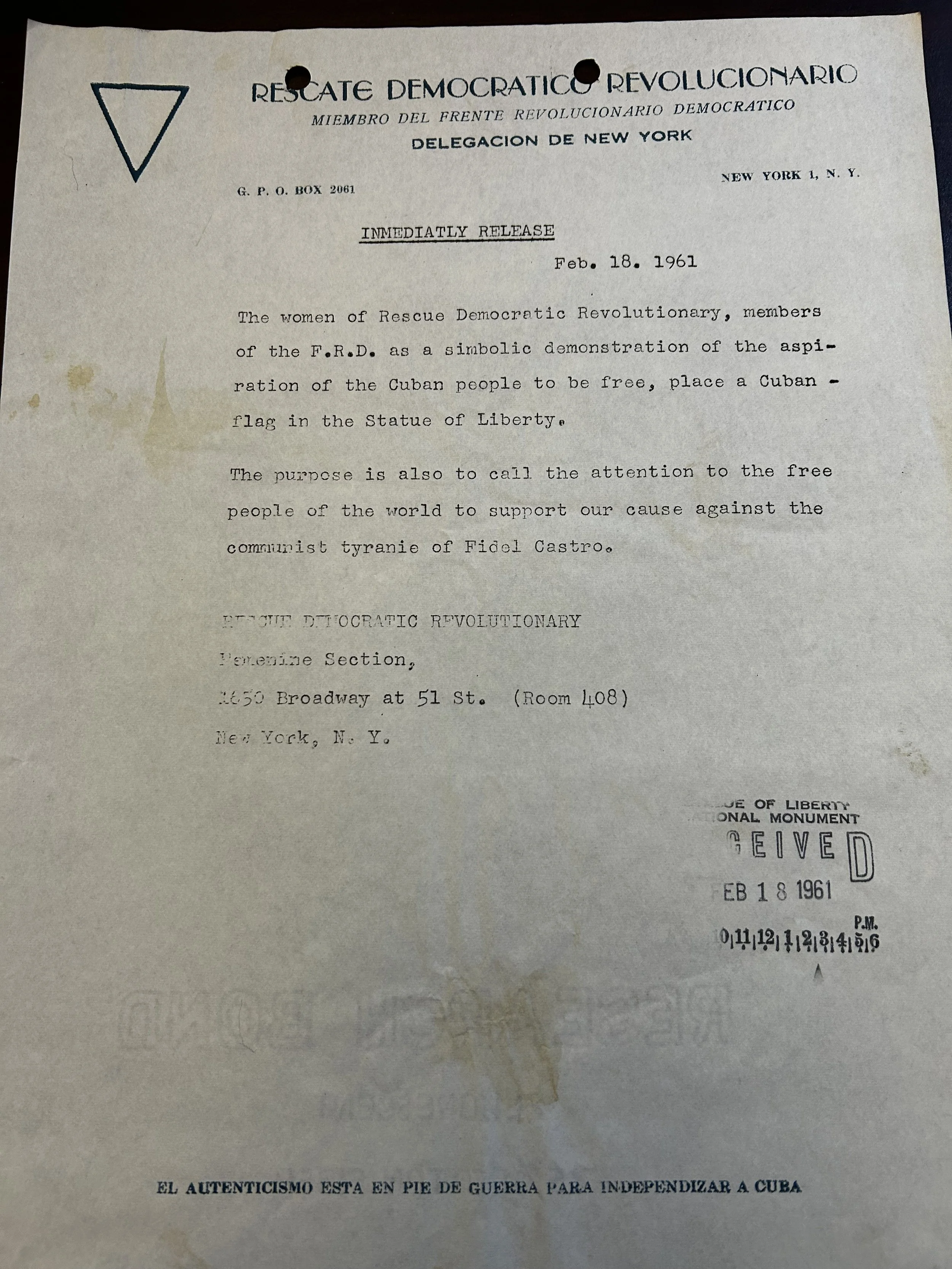

Statement of intent to place a Cuban flag at the Statue of Liberty by the Rescue Democratic Revolutionary delegation of New York

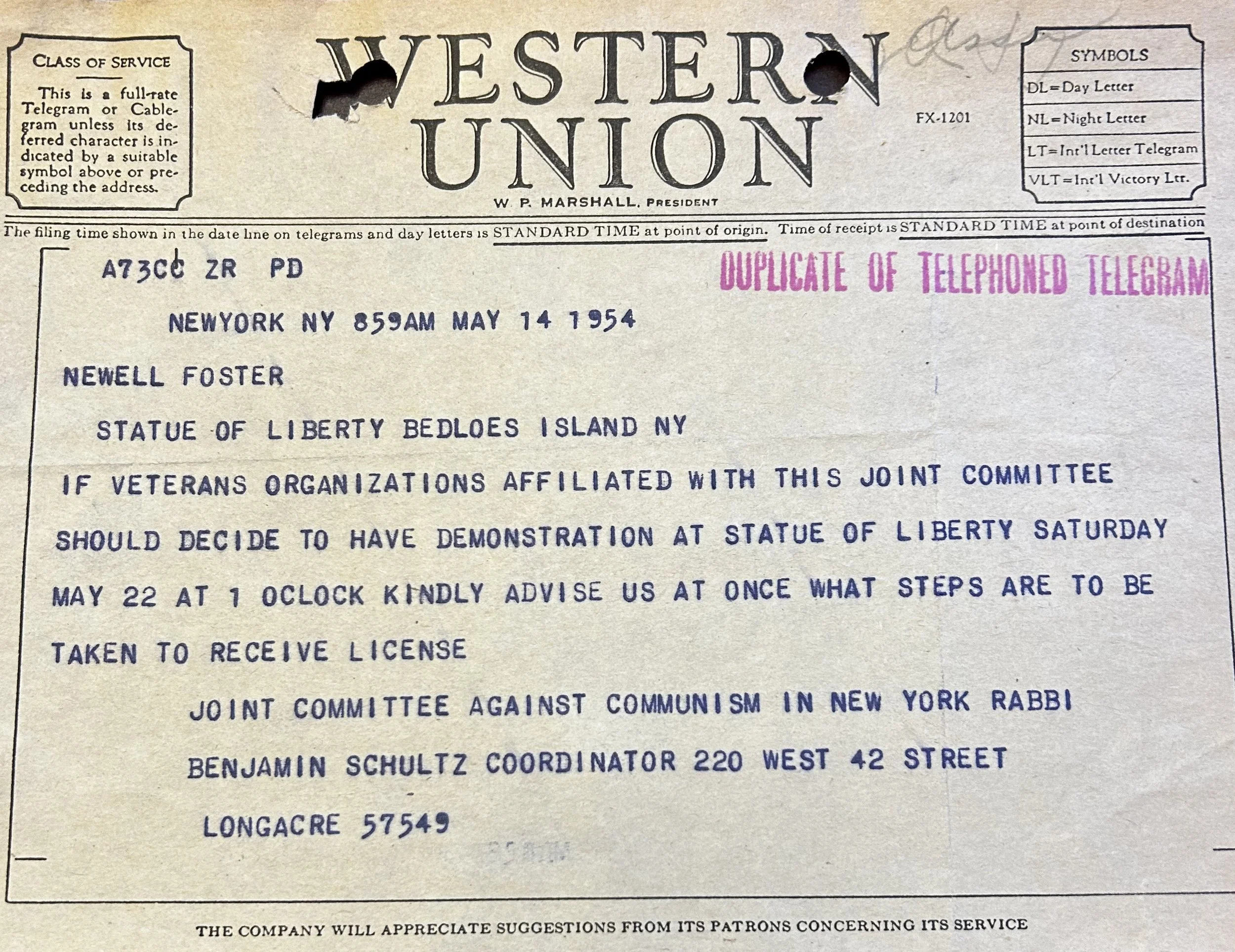

Telegram from the Joint Committee Against Communism in New York regarding permission of the Emma Lazarus Federation of Jewish Women's Clubs to hold an event at the Statue of Liberty

Further Stories and Resources

-

Since the takeover of Puerto Rico in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, many Puerto Rican activists have pushed for independence from the United States. Two incidents in the 1950s led to the indefinite imprisonment of several Puerto Rican independence activists and, more than twenty years later, former members of the Young Lords Party who had formed the Committee for the Freedom of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Prisoners decided to occupy the Statue of LIberty to protest their long incarceration. The Young Lords Party were a group of Puerto Rican independence activists that included Miguel “Mickey” Melendez, Juan Gonzalez, Denise Oliver-Velz and Iris Morales. Dedicated to helping the Puerto Rican community in New York and to independence for Puerto Rico, the Young Lords Party was an offshoot of the original Young Lords in Chicago, and were profoundly influenced by the Black Panthers, and maintained close ties with the Panthers in the early 1970s.

The Committee activists chose October 30 as the day for the occupation–the anniversary of the nationalist uprising in Jayuya, Puerto Rico in 1950. Twenty-eight activists took the first tourist ferry from Battery Park and raced ahead of the other passengers when they docked at Liberty Island. Unarmed, they secured the State of Liberty, and ordered park rangers and tourists to leave without the use of violence. After barricading themselves in the Statue’s base, they made their way to the crown and hung a huge Puerto Rican flag off the Statue. One of the group who had intentionally stayed behind, staged a press conference at Battery Park and presented demands for the release of the Puerto Rican prisoners. At the end of the day, a special SWAT team broke through the barricaded door and arrested the unresisting activists, who were taken off the island and later charged with criminal trespass. All of the activists were released and later fined, and the independence fighters imprisoned in the 1950s were finally granted clemency by President Carter in 1979.

More information:

Melendez, Manuel “Mickey” (2005). We Took to the Streets. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

-

In 1964, Robert Collier and a group of students visited Cuba against the U.S.-imposed embargo. When Collier returned to New York, the experience prompted him to begin a group–the Black Liberation Front–not to be confused with other Black Liberation Fronts elsewhere (e.g., the BLF in Great Britain). Collier was joined by other activist colleagues, including Walter Bowe and Khaleel Sayyed, who were also in the security detail of Malcolm X. Finally, the group was joined by another activist–Raymond Wood–-who was, in fact, undercover police working for the NYPD’s “BOSSI” (Bureau of Special Services and Investigations) division. Wood had previously infiltrated the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and taken the role of provocateur–encouraging members to commit illegal acts with the ultimate goal of discrediting Black activism. Defendants in the trial later argued that the plot to blow up the Statue of Liberty came from Wood himself.

Together with Wood, the young activists got in touch with Michelle Duclos, a Quebec separatist, who agreed to supply them with dynamite. In February of 1965, Duclos drove down from Montreal, parked the car at a public lot, and concealed the dynamite.The next morning, Wood and Collier went there to retrieve the dynamite, and were promptly arrested. Duclos later testified against the three Black activists for a reduced sentence, and Wood was promoted to detective.

The outlandish quality of the plans, which included not only bombing the State of Liberty, but the Liberty Bell (in Philadelphia) and the Washington Monument (in D.C.), together with the strangeness of a Quebec separatist assisting in the scheme, have given rise to many theories. One of them comes from an apparent deathbed confession from Wood, who regretted his role in the bomb plot because it removed two people from Malcolm X’s security detail (Walter Bowe and Khaleel Sayyed). A few days after the arrests of Collier and company, Malcolm X was assassinated.

So was the NYPD involved? While the theory remains controversial, what is indisputably true is that law enforcement at all levels worked to weaken African American civil rights activism in the U.S., and they did so using a variety of non-legal means.

Sources:

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/173226

https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/when-the-cops-were-spies-and-the-terrorists-were-everywhere