The Statue of Liberty

in Black Culture, Protest and History

Due to its symbolic meaning as a symbol of democracy and freedom, the Statue of Liberty has been the site of protests through time, particularly from Black civil rights activists as well as many other groups. In addition, there are those who maintain that the statue was originally designed by its French creators using a Black female model (see below). Regardless, as seen in many of the visual clippings and correspondence below, many groups have sought permission to protest at the statue. Many have protested without permission. And, many argued that certain groups should not be allowed to use the statue as a symbolic backdrop for their beliefs and ideologies.

The changing meanings of the Statue of Liberty over time can tell us much about the changing prerogatives of the state. Initially, the statue emphasized abolition, with both French creators Laboulaye and Bartholdi supporting emancipation and lauding the possibility of a democracy of the people. In the years after the dedication of the statue in 1886, however, that meaning shifted away from African Americans and towards immigration and, in the midst of World War I, towards national unity against the Central Powers. It remained symbolic of immigration throughout the twentieth century. It is no mistake that the American Museum of Immigration was established there in 1972, where it continued until 1991–although its tenure on Liberty Island was punctuated with protests and concerns over its failure to acknowledge the histories of non-white peoples in the United States.

The images below represent some of the images and press clippings that correspond to further resources and stories further down on the page.

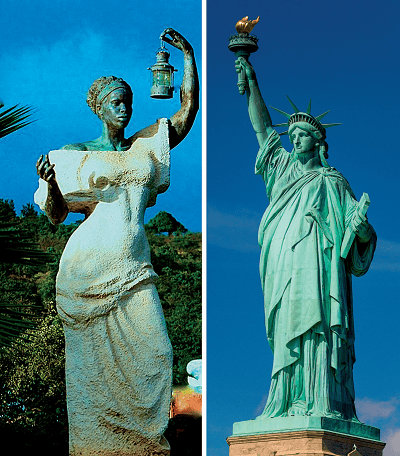

An early rendering bolstering the notion that the Statue of Liberty was based on a Black woman

Bartholdi's original proposed site for the statue [Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

Statue of Liberty Centennial Celebration [By Emmett Francois - This image was released by the United States Department of Defense with the ID DN-ST-87-01292. Public Domain

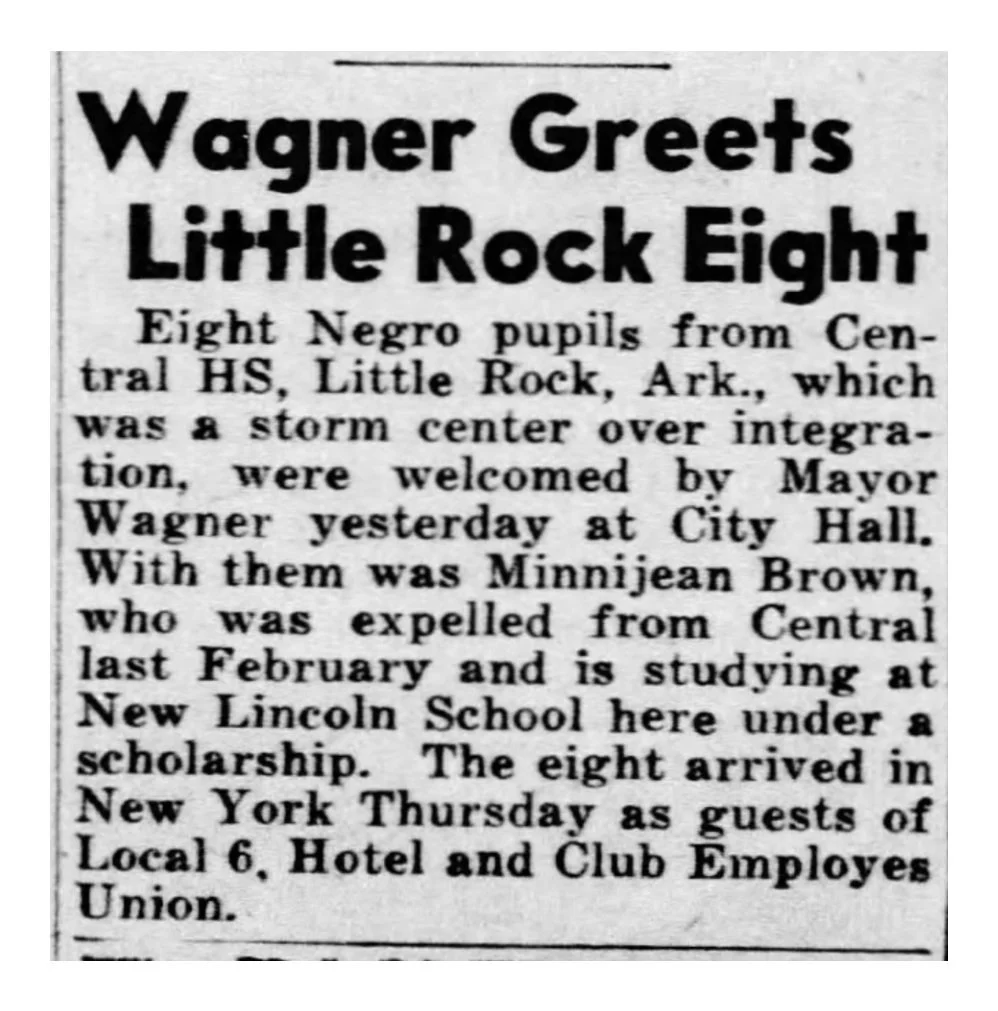

Press Clipping: The Little Rock 9 visit New York and the Statue of Liberty

Harry Belafonte at an MLK remembrance at the Statue of Liberty

Harry Belafonte delivering speech during an MLK remembrance at the Statue of Liberty

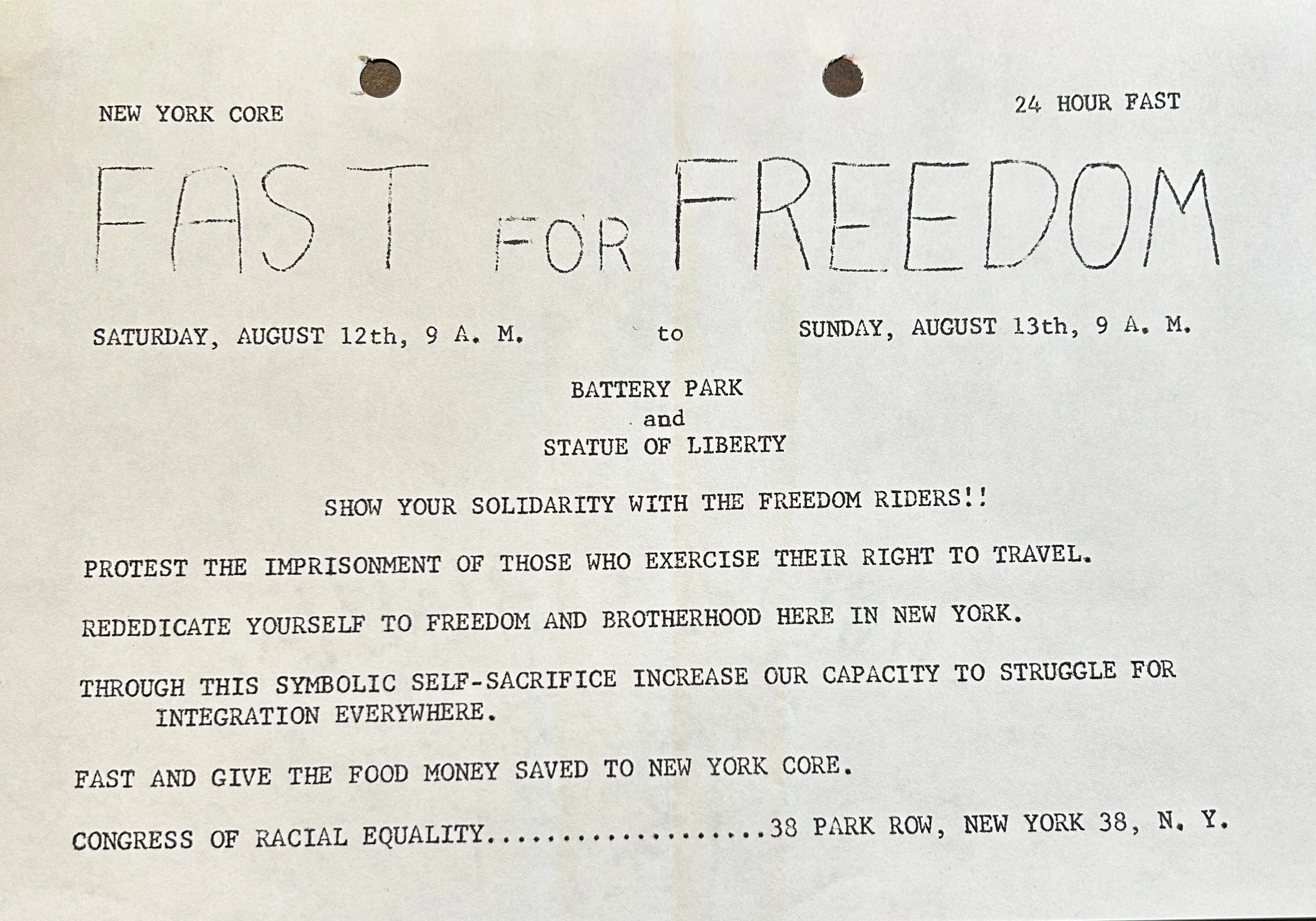

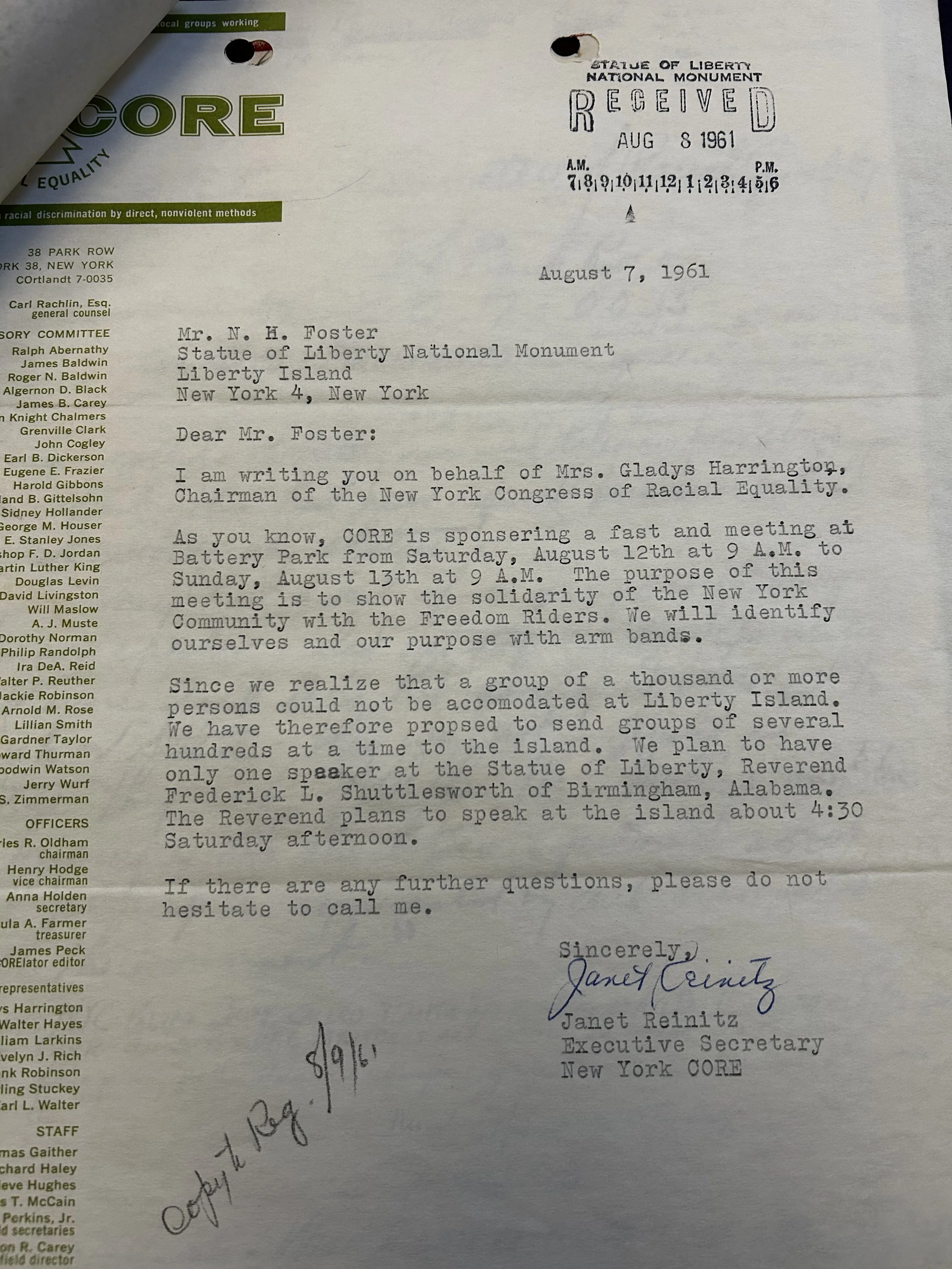

An element of communication for the 'Fast for Freedom' protest at the Statue of Liberty by the Congress of Racial Equality

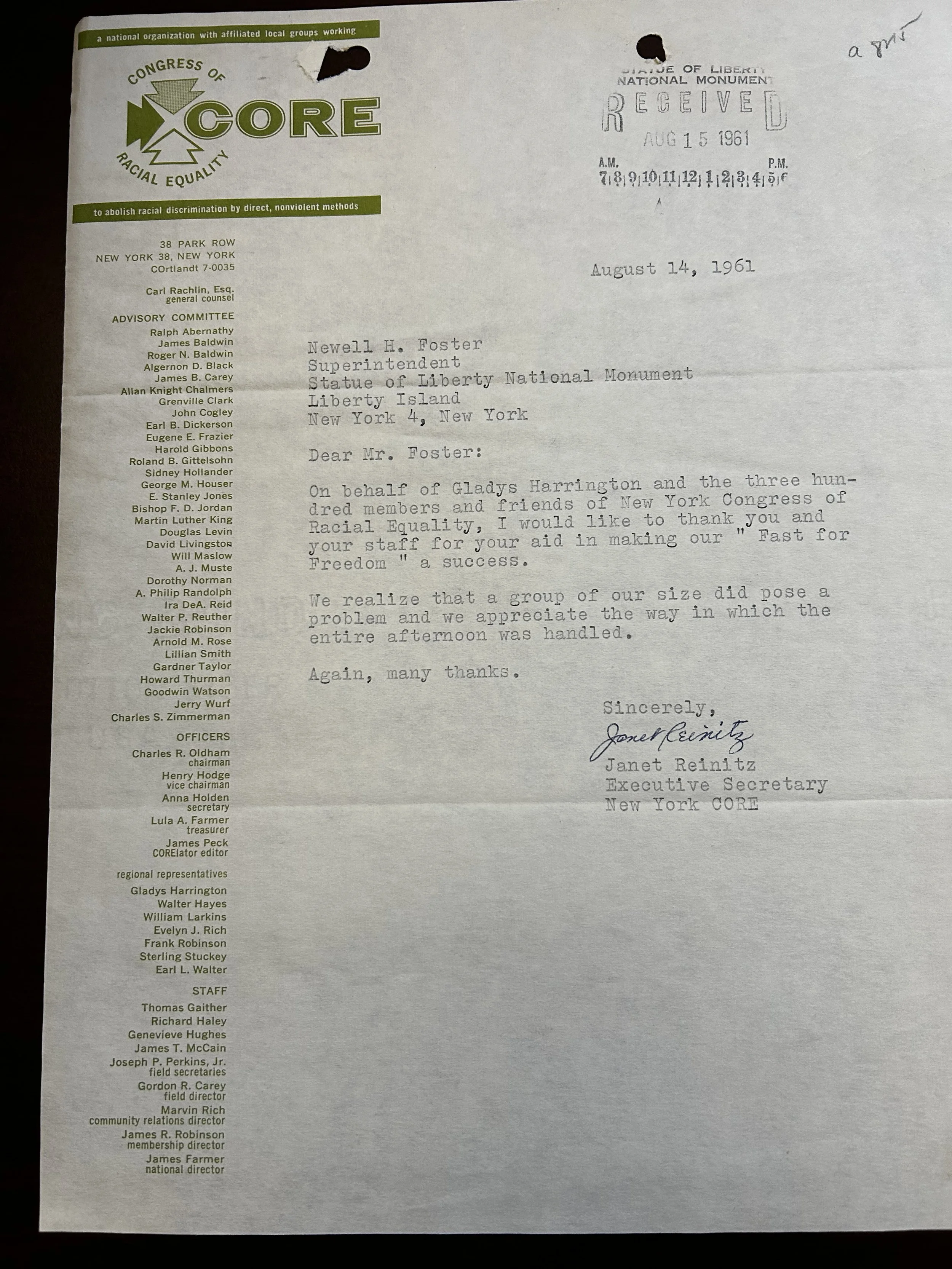

Thank you letter to the National Park Service by the Congress of Racial Equality for the 'Fast for Freedom' protest at the Statue of Liberty

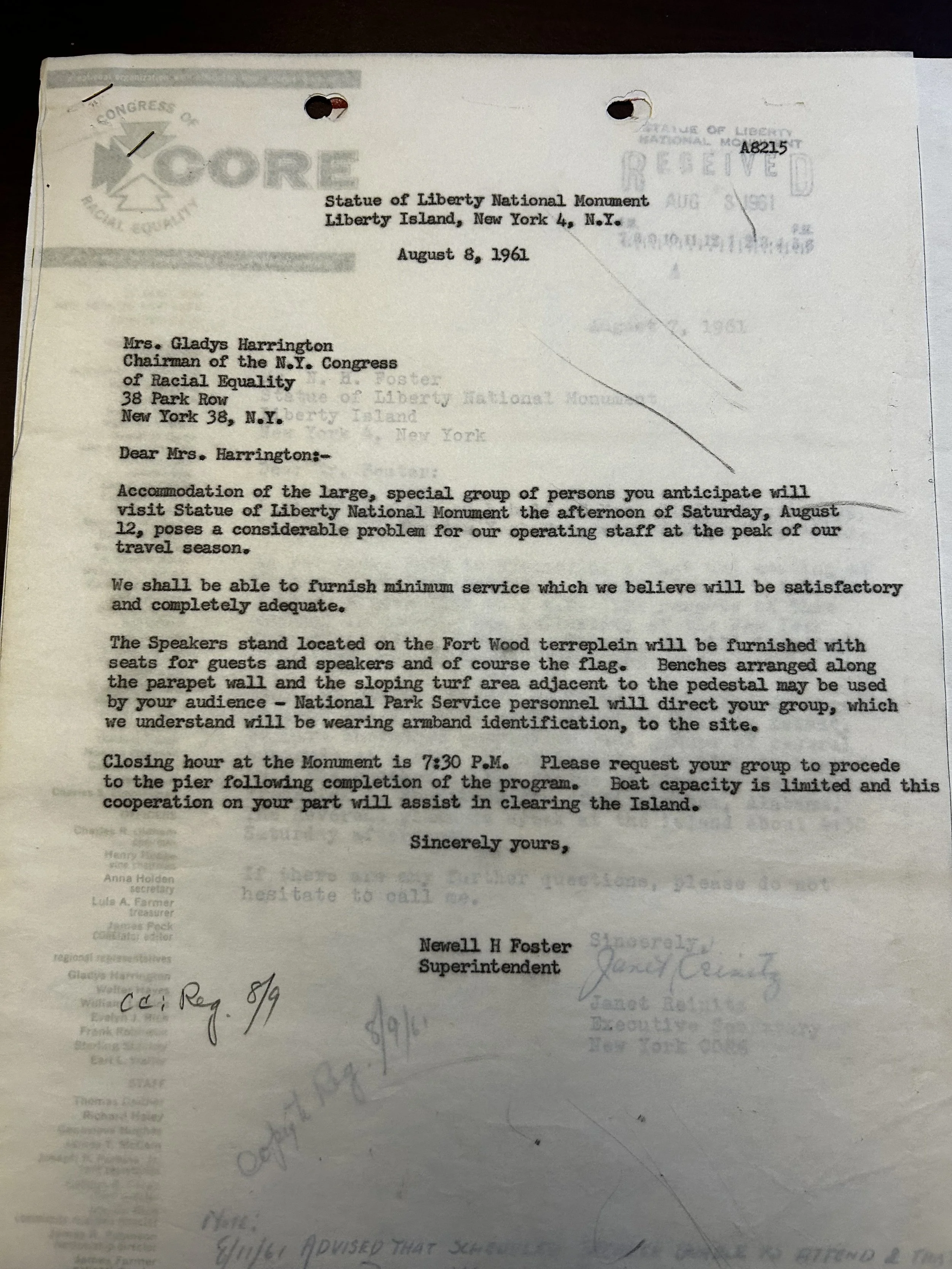

Letter from Statue of Liberty superintendent to the Congress of Racial Equality granting permission and logistics for the 'Fast for Freedom' protest

Letter of clarification to the Statue of Liberty National Park Service superintendent clarifying size of crowd asking permission to go and speak at Liberty Island

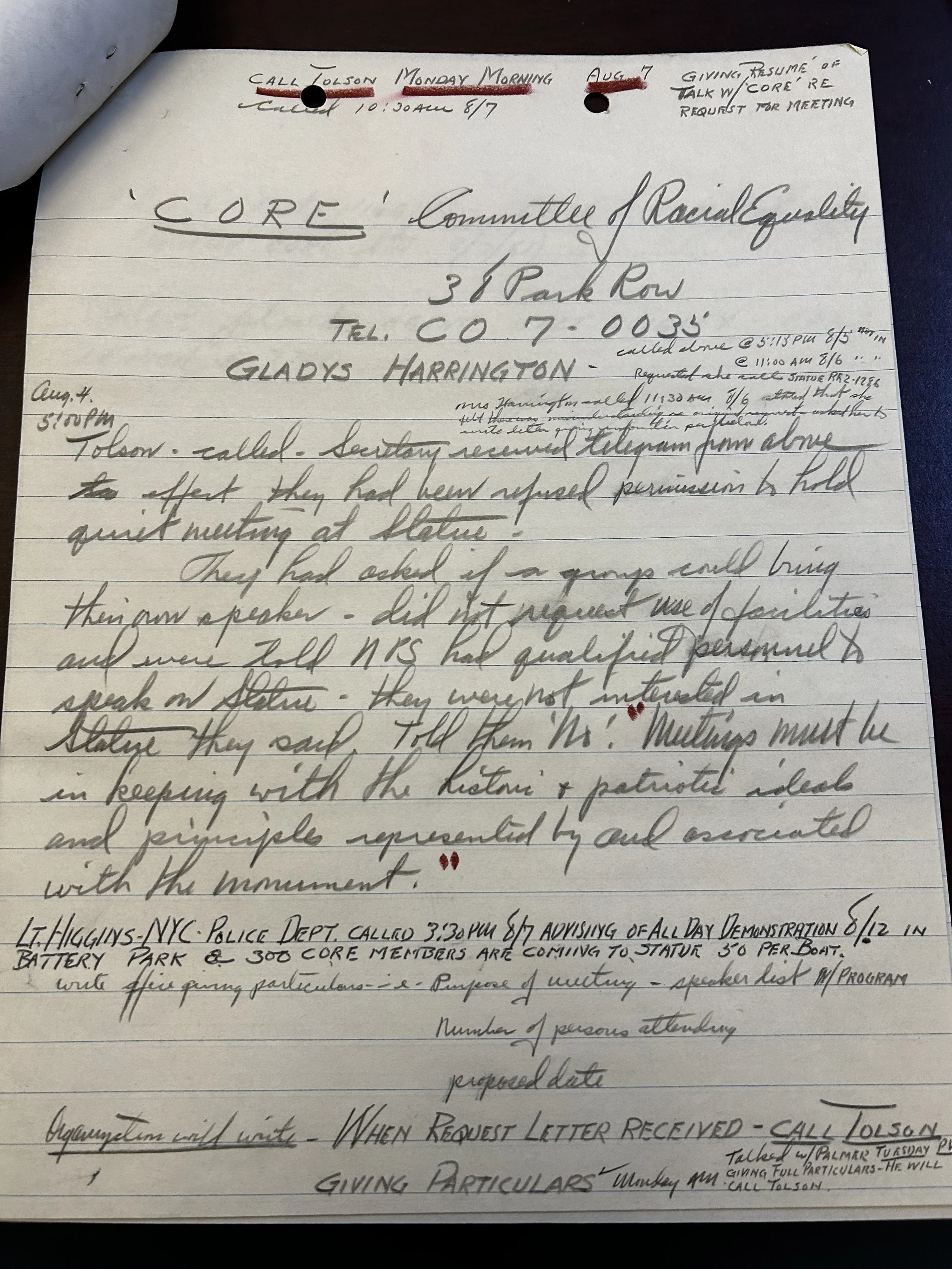

Draft of letter Congress of Racial Equality

Letter from the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King Jr. and the Struggle for Freedom in the South seeking permission to stage a protest at the Statue of Liberty with original signatures from co-chairs Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier

Further Stories and Resources

-

In the late 1990s, the National Park Service commissioned a report to investigate persistent internet postings claiming that the Statue was based on an African model, that it was meant to commemorate African American troops in the Civil War, and other interpretations. The report, released in 2000, debunks some popular myths about the statue. Yes, Bartholdi had proposed a colossal monument, “Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia,” to the khedive Isma’il Pasha in 1867, and that figure was based on an Egyptian peasant woman. It was never built, but the sketches are thematically similar to the State of Liberty. Nevertheless, Bartholdi’s model for “Liberty Enlightening the World” seems to have been a French woman, although there have been several theories over the decades, including Auguste Bartholdi’s mother, members of the French aristocracy and a French peasant. The Statue also incorporated thematic elements from abolitionist images, including broken chains–featured on many abolitionist coins and medallions.

Today, the controversy continues through social media, with conversations on different platforms periodically reviving the “Black Statue of LIberty” thesis. While this may not be the case, it is certainly true that the Statue was originally meant to symbolize freedom from oppression, the triumph of the Union in the U.S. Civil War and, broadly, the struggle of oppressed peoples everywhere.

References

Joseph, Rebbeca, Brooke Rosenblatt and Carolyn Kinebrew (2000). “THE BLACK STATUE OF LIBERTY RUMOR: An Inquiry into the History and Meaning of Bartholdi’s Liberté éclairant le Monde.” Washington, D.C.” National Park Service.

Smothers, Ronald (1986). “Liberty Gala Stirs Mixed Emotions for Blacks.” New York Times, 5/30/86: A1, D19.

https://www.historians.org/presidential-address/tyler-stovall/

-

Plans for a large-scale renovation of the Statue of Liberty began in the 1970s, and coalesced around the establishment of what would become the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan appointed then-Chrysler Motors CEO Lee Ioccoa as the Chair of the Foundation, and fundraising accelerated, along with plans for a massive centennial celebration in July of 1986. Events over the course of 4 days would include concerts, speeches, ship regattas, blimp races and historical reenactments and were to be held on Liberty Island, in Manhattan and in Liberty State Park in New Jersey. All of the events emphasized a central theme: successful immigrants and the definition of the “American Dream” as financial success.

The planning process was not, however, without controversy. Black activists noted that the Centennial celebration represented US history as the story of immigrants, and avoided the history and legacy of enslavement altogether. The historian John Hope Franklin told the New York Times that “It’s a celebration for immigrants and that has nothing to do with me” (Smothers 1986: A1). The Schromburg Center presented an exhibit on Afro-Caribbean immigration, and defenders of the Centennial noted that many Black entertainers and notables were included in Centennial events.

Whatever the case, the Centennial Celebration marked the completion of a transformation that began in the early 20th century away from the Statue’s abolitionist roots to a symbol of entrepreneurial, immigrant success–the union of individualism and capitalism that was a hallmark of the Ronald Reagan years in the 1980s.

-

Despite the 1954 Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka ruling that integrated schools in the United States, many local- and state governments resisted integration–especially in the South, where segregation remained popular among whites. In September of 1957, nine Black students attempted to attend Central High School in Little Rock Arkansas and were stopped by the National Guard under orders from the Governor Orval Faubus.

Two weeks later, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the National Guard in Arkansas and sent U.S. troops into Little Rock. The students attended class beginning on September 25, 1957, enduring countless racist threats and taunts from the white students and white residents of Little Rock. One of the nine, Minnijean Brown, was expelled later that year after a series of racist acts against her. She was given a scholarship to an experimental high school in Manhattan. In he summer Of 1958, the New York Hotel Workers’ Union raised money to bring the “Little Rock Nine” (including Minnijean Brown) to New York to accept a “Better Race Relations” award, and to see the sights of New York. Included in the itinerary was Liberty Island, the only federal site.

-

In his 1965 “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon,” Baldwin’s narrator is an expatriate, African American celebrity returning to the United States from Paris for the first time in years. He is decidedly ambivalent about the trip–taken because of his mother’s death–but is still able to generate some nostalgic feelings for the U.S. As the ship nears New York, the narrator accompanies other passengers to the deck, where he observes their delight.

“I watched their shining faces and wondered if I were mad. For a moment I longed, with all my heart, to be able to feel whatever they were feeling, if only to know what such a feeling was like. As the boat moved slowly into the harbor, they were being moved into safety. It was only I who was being floated into danger. I turned my head, looking for Europe, but all that stretched behind me was the sky, thick with gulls. I moved away from the rail. A big, sandy-haired man held his daughter on his shoulders, showing her the Statue of Liberty. I would never know what this statue meant to others, she had always been an ugly joke for me” (1965: 163).

The narrator seems to share many of Baldwin’s own experiences; he expatriated to Paris in 1948, returning to New York in 1957–and then moving back to France in the 1970s. Asked about the meaning of the Statue in Ken Burns’s 1985 documentary, “The Statue of Liberty” Baldwin replies: “For Black Americans...the Statue of Liberty is simply a very bitter joke, meaning nothing to us.” His point takes him back to the Declaration of Independence, with its call for “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” that–in 1776–did not include Black people. By the 1970s, Baldwin’s work for civil rights, and his depression following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and many others, were factors in his decision to move back to France.

References

Baldwin, James (1965). Going to Meet the Man. New York: Vintage.

![Bartholdi's original proposed site for the statue [Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66a1626cba1f8c73183ec0cd/d8ce87ce-3d42-4c39-87b6-88bae26d2043/BlackSOL.jpg)